A staged work for voices, ensemble,

sound producing machines, projection, space and light

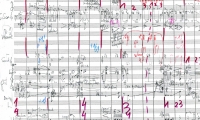

Concept & Music

Clemens Gadenstätter

Text | Libretto

Lisa Spalt

Sound producing machines

Jakob Scheid & Christian Blom

Conductor

Georges-Elie Octors

about Nerone

With a lyre in his hand he sings of Rome as it burns. Although this scene probably never happened, it still shapes perception of a historical figure who is just as famous and notorious in the present day – Nero, the Roman Emperor from 54 to 68 AD. A far-sighted conqueror, Olympian and multi-talented artist on one hand, and a murderer, arsonist, antichrist and megalomaniac on the other. It is these very contrasts and discrepancies which emerge from the contradiction of the “sensitive monster” that make Nero so fascinating. The real subject as a hard-wearing screen that is projected onto – everyone has their “own” Nero.

Clemens Gadenstätter tackles the potential as well as the complications of this conflicting interpretation in his stage play Nerone. Nero here is both himself and his various representations – emperor and artist at the same time and in the same place. The subject and setting of Nerone is therefore the stage which does not just refer to the theatrical space. Instead, Gadenstätter extends the stage towards contemporary everyday perception and experience. Beyond the sphere of the representative “play”, it becomes an ambiguous space of action and drama, constantly fluctuating between authenticity and semblance and between the factual and narrative.

Existing simultaneously in various (social) spheres, roles and functions and adapting to these environments mimetically has long been part of the modern human condition. Meeting the challenge of this complete engagement requires a certain willingness to demonstrate a “split personality”. We are just as much real as virtual and act directly but equally so through media. In Nerone a historical figure becomes a symbol of this “art of metamorphosis”. Various constellations of a game of deception between identities are explored in four “dramatic acts”. Nero appears in various contexts in these scenes – as an actor playing the part of the emperor, as an Olympian who abuses the noble games for self-aggrandisement, as an observer of the Great Fire of Rome and as a statue of the petrified guardian of the Domus Aurea.

The fire scene in particular imbues the play with identity, reality and fiction which Clemens Gadenstätter allows to unfold in Nerone. The Great Fire of Rome is staged from different perspectives – Nero, who watches the burning city, Nero, who writes an epic poem about the Burning of Troy as an allegory for Rome ablaze and finally the experience of the actual fire by the Roman citizens. The scene therefore appears simultaneously in three versions – as an aesthetic object, as an allegory and as brutal reality.

Nerone is a piece that constantly touches upon borderlines. Nothing is clear from the outset or reducible to a specific meaning. In contrast, every action is always the representation of another. The play’s principal concept is that of a space that, on one hand, influences the action that takes place within it but, on the other, is also shaped by each of those actions. This interaction opens up a wide range of possibilities for working with different media – music, sound, language, text, narration, images and film. No element stands alone but is instead always part of an interaction.

In Nerone, Gadenstätter creates musical and theatrical situations in which he puts his aesthetic concept for illuminating the semantic qualities of music in contexts that are as multifaceted as it is possible to conceive. The audience is put under a spell of the most heterogeneous perceptions and challenged to continually adopt new positions. Nero is a fleeting fixed point. He conquers the audience and makes them a participant in his imponderable staging. “Nerone”, explains Clemens Gadenstätter, “is a means of presenting theatre in the theatre but at the same time the terrifying reality of our modern world.”

Four Dramatic Knots

1

Nero, an actor that mimes the Emperor

The audience acts like an audience, but is at the same time subject to the Emperor’s decisions – as well as those portrayed? (the projection?) as the real one. This scene deals with the inescapability and brutality of the mixture of representation and reality. What happens, when the border blurs between an action as expression of an existential necessity and one as a delusion of another, when effects of representation and those real actions are seen as equal?

2

The Olympic games, all of them won by Nero

Nero is not uneducated in the required disciplines, but he is in fact not an Olympian. Through corruption he creates a situation in which the ritual of contests are transformed into an “as-if”; a demonstration of real power and godlike insanity.

The sporting ritual, that was founded to strengthen the social and political framework is on the next level to where it is placed by the real power of Nero, “just/no better than a ritual”; the real, in the ritual captured fight (like a fly in amber) suddenly gets to the re-enactment of a competition following a script. Nero’s power is in this expression admitted in reality, but he holds himself up to ridicule by declaring it to a theatre audience. Representation is reduced to illustration. Within the imitation the holy ritual becomes a harlequinade in which a self-representing Nero kills real humans. In structural terms the competition will be between the “mechanical” musician and the musicians of the ensemble, always won by the mechanical one.

3

Rome burning

This is perverted by Nero into a play by singing his own epos of the fire of Troya while watching the burning city from afar. He correlates the representation given by the Illias of this event with this other one, the fire of Rome, through which he opens a space of total inauthenticity. In this space he sees the drama taking place for real in front of his eyes as “real fiction”: he staged this spectacle. Nero’s decisions concerning the re-building of the city after the fire make the simultaneous presence of both levels of reality clear: sophisticated fire precautions should shelter his “Domus Aurea” which will be the stage of his further plays and events, a scenery/decor in which he will continue to live on.

The fire of Rome will be staged from various perspectives at the same time: Nero watching the burning city, Nero singing the epos of Troy burning in the form of an allegory, the reality of the fire experienced by the Roman citizens. The scene will be simultaneously staged as an aesthetic object, an allegory and a brutal reality.

4

Nero’s “Domus Aurea”, which is planned as a theatre/playhouse

Here the parks are planned as “luna parks” for Roman citizens. A 40 metre high colossus in the centre illustrates him in “divine nudity”. The living environment becomes a stage. The multiple fractured aspect of space is emphasised here as an artistic object: the house as a space for different social spaces, for various uses (an emperor’s villa and luna park etc.) and as a pure aesthetic object. All qualitative aspects of spatiality are at the same time actual ones (Nero’s apartment and the centre of his power) as well as figurative ones (the staging of the actual one).

over Nerone

Met een lier in de hand bezingt hij Rome terwijl de stad in lichterlaaie staat. Waarschijnlijk is dat een verzonnen tafereel, maar toch vormt het de perceptie van een historische figuur die nu nog altijd beroemd en berucht is – Nero, keizer van het Romeinse Rijk van 54 tot 68 na Christus. Een vooruitziende veroveraar, een olympiër en een getalenteerde kunstenaar enerzijds en een moordenaar, brandstichter, duivel en megalomane gek anderzijds. Precies die contrasten en tegenstrijdigheden zitten vervat in de beschrijving van Nero als een “gevoelig monster” en maken hem zo fascinerend. De echte mens als een duurzaam scherm waarop alles geprojecteerd wordt – iedereen heeft zijn “eigen” Nero.

In zijn theaterstuk Nerone verdiept Clemens Gadenstätter zich in het potentieel en de complicaties van deze tegenstrijdige interpretatie. Nero speelt zowel zichzelf als de verschillende functies die hij vervult – keizer en kunstenaar, op hetzelfde moment en op dezelfde plek. Daarom is het toneel het onderwerp van en de setting voor Nerone, maar het toneel is ruimer dan alleen de ruimte waar gespeeld wordt. Gadenstätter breidt het toneel uit naar de moderne perceptie en ervaringen van elke dag. Het reikt verder dan het traditionele “toneelstuk”, het wordt een ambigue ruimte met actie en drama, die constant heen en weer gaat tussen authenticiteit en schijn, en tussen wat echt is en verteld wordt.

Tegelijkertijd in verschillende (sociale) kringen, rollen en functies bestaan en je aan die omgevingen aanpassen door ze te kopiëren is allang een deel van het moderne mens-zijn. Om de uitdaging van dat allesomvattende engagement aan te kunnen, moet je bereid zijn een “gespleten persoonlijkheid” te ontwikkelen. We zijn net zo goed echt als virtueel en reageren rechtstreeks maar ook via andere kanalen. In Nerone wordt een historische figuur een symbool van deze “kunst van de metamorfose”. In een spel van misleiding tussen identiteiten worden in vier “dramatische bedrijven” verschillende constellaties verkend. In die scènes verschijnt Nero in verschillende contexten – als een acteur die de rol van keizer speelt, als een olympiër die de edele spelen misbruikt voor het vergroten van zijn macht, als een toeschouwer bij de grote brand van Rome en als een standbeeld, de versteende bewaker van het Domus Aurea.

Vooral in de scène met de brand staan identiteit, werkelijkheid en fictie centraal, de kernelementen die Clemens Gadenstätter in Nerone aan bod laat komen. De grote brand van Rome wordt vanuit verschillende perspectieven belicht – Nero die toekijkt hoe de stad brandt, Nero die een episch gedicht schrijft over de brand van Troje als allegorie voor de Romeinse vuurzee, en tot slot de manier waarop de Romeinse burgers de brand ervaren. Daarom is deze scene in drie versies tegelijkertijd te zien – als een esthetisch object, als een allegorie en als de meedogenloze werkelijkheid.

Nerone is een stuk dat constant grenzen overschrijdt. Niets is van in het begin duidelijk of kan tot een eenduidige betekenis herleid worden. Integendeel, elke actie is altijd een afspiegeling van een andere. Het stuk is geconcipieerd als een ruimte die enerzijds de actie beïnvloedt die zich in die ruimte ontwikkelt, maar anderzijds ook gevormd wordt door die zelfde acties. Die interactie biedt een waaier van mogelijkheden om met verschillende media te werken – muziek, geluid, taal, tekst, vertellingen, beelden en film. Geen enkel onderdeel staat op zichzelf, het maakt altijd deel uit van een interactie.

In Nerone creëert Gadenstätter muzikale en dramatische situaties waarin hij zijn esthetische ideeën verwerkt en de semantische kwaliteiten van muziek illustreert in contexten die eindeloos veelzijdig en fantasierijk zijn. Het publiek wordt betoverd door sterk uiteenlopende percepties en het wordt uitgedaagd om zich telkens weer aan nieuwe situaties aan te passen. Nero is een vluchtig vast punt. Hij onderwerpt het publiek en maakt het tot een deelnemer in zijn onvoorspelbare toneelspel. “Nerone”, zo legt Clemens Gadenstätter uit, “is een manier om theater te laten zien in het theater en tegelijkertijd een beeld te schetsen van de angstaanjagende werkelijkheid van onze moderne wereld.”

Vier Dramatische Knopen

1

Nero, een acteur die de Keizer nabootst

Het publiek gedraagt zich zoals een publiek, maar tegelijkertijd is het onderhevig aan de beslissingen van de Keizer – zowel degene die geschetst worden (de projectie?) als de echte. Dit bedrijf verdiept zich in het feit dat de vermenging van een voorstelling van iets en de werkelijkheid onontkoombaar en wreed is. Wat gebeurt er wanneer de grens vervaagt tussen een daad als uiting van een existentiële noodzaak en een daad ten gevolge van de valse voorstelling van een andere daad, wanneer de gevolgen van de voorstelling van die daden en de echte daden als gelijkwaardig worden beschouwd?

2

De Olympische Spelen, alle disciplines gewonnen door Nero

Nero is wel onderlegd in de vereiste disciplines, maar hij is geen olympiër. Door corruptie creëert hij een situatie waarin het ritueel van de wedstrijden tot een klucht wordt herleid; een demonstratie van pure macht en goddelijke waanzin. Het sportritueel, dat werd ontwikkeld om het sociale en het politieke weefsel te versterken, verhuist door de onversneden macht van Nero naar een nieuw niveau, dat van “enkel/niet meer dan een ritueel”; de echte, in het ritueel vervatte strijd (zoals een vlieg in amber) verwordt tot het naspelen van een wedstrijd die nauwkeurig vastgelegd is. Door die zin wordt Nero’s macht in de werkelijkheid erkend, maar hij maakt zichzelf belachelijk door die tegenover het theaterpubliek uit te spreken. De voorstelling wordt herleid tot een illustratie. In de imitatie wordt het heilige ritueel een dwaze vertoning waarin Nero zichzelf speelt en echte mensen doodt. Structureel gezien gaat de wedstrijd tussen de “mechanische” muzikant en de muzikanten van het orkest, waarbij men op voorhand weet dat de mechanische muzikant zal winnen.

3

Rome brandt

Dat wordt door Nero verdraaid tot een toneelstuk wanneer hij zijn eigen epos over de brand van Troje zingt terwijl hij van ver toekijkt hoe de stad brandt. Hij linkt de beschrijving uit de Ilias van die brand met de brand van Rome en opent zo de deur naar totale inauthenticiteit. Hij ziet het drama zich voor zijn ogen in het echt afspelen en noemt het “pure fictie”: hij heeft dat spektakel geënsceneerd. De beslissingen die Nero na de brand neemt om de stad weer op te bouwen geven aan dat de werkelijkheid op twee niveaus tegelijkertijd speelt: geavanceerde brandbeveiligingsmaatregelen moeten zijn “Domus Aurea” beschermen, de plek die het toneel zal zijn van zijn volgende toneelstukken en evenementen, een omgeving/decor waarin hij zal voortleven. De brand van Rome zal tegelijkertijd vanuit verschillende perspectieven getoond worden: Nero die toekijkt hoe de stad brandt, Nero die als allegorie het epos van het brandende Troje bezingt, de echte brand zoals de burgers van Rome die ervaren. De gebeurtenis wordt simultaan verbeeld als een esthetisch iets, een allegorie en de harde realiteit.

4

Nero’s “Domus Aurea”, ontworpen als toneel/schouwburg

In dit bedrijf worden parken ontworpen als “pretparken” voor de burgers van Rome. In het midden staat een 40 meter hoge kolossus, een beeld van Nero in “goddelijke naaktheid”. De levende omgeving wordt een toneel. Het veelzijdige, gedifferentieerde aspect van de ruimte wordt duidelijk gezien als een artistiek voorwerp: het huis is een ruimte voor verschillende sociale ruimtes, gebruikt voor verschillende doeleinden (de villa van een keizer, een pretpark enz.) en ook een zuiver esthetisch iets. Alle kwalitatieve aspecten van ruimtelijkheid zijn tegelijkertijd echt (Nero’s vertrekken en het centrum van zijn macht) en symbolisch (van die ruimte een toneel maken).

À PROPOS DE NERONE

La lyre à la main, il chante Rome en proie aux flammes...

Bien que cette scène soit très vraisemblablement fictionnelle, elle a contribué à façonner une figure historique qui n’a rien perdu aujourd’hui de sa puissance d’impact : Néron, Empereur de Rome,54 — 68.

Conquérant avisé, sportif olympique et artiste aux talents multiples d’une part ; meurtrier, pyromane, antéchrist et mégalomane de l’autre... ce sont précisément les contrastes et les contradictions propres à la personnalité de ce « monstre sensible » qu’est Néron qui le rendent fascinant. Sans doute fonctionne-t-il comme un écran de projection aux ressources inépuisables : chacun a son Néron « à lui».

Dans sa pièce de théâtre, Clemens Gadenstätter vise le riche potentiel — et ses complications — qui peuvent naître de ces interprétations conflictuelles. Ici, Néron est à la fois lui-même et ses représentations, il est empereur et artiste au même moment, au même endroit. « La scène » n’est pas que le cadre de ce Nerone, elle en est aussi bien le sujet. Au-delà de l’espace théâtral, Gadenstätter étend ce cadre à la perception et à l’expérience quotidienne contemporaine. Au-delà de la sphère de la « pièce » représentative, il devient un espace ambigu d’action et de drame, fluctuant constamment entre vérité et semblant, entre factuel et narratif.

Étant donné que nous évoluons simultanément dans différentes sphères sociales, les rôles, les fonctions et l’adaptation mimétique à nos environnements font, depuis longtemps, partie intégrante de la condition humaine. Pour relever le défi de cet engagement total, nous devons faire preuve d’une certaine volonté de « dédoublement de personnalité ». Nous sommes tout aussi réels que virtuels, nous agissons autant en direct qu’au travers de médiatisations. Dans Nerone, la figure historique de l’empereur devient le symbole de cet « art de la métamorphose ». Au fil de quatre « actes dramatiques », différentes constellations de ce jeu d’illusion identitaire sont explorées. Néron apparaît dans des contextes variés : acteur jouant le rôle de l’empereur, olympien abusant des jeux nobles pour s’auto-glorifier, observateur du Grand incendie de Rome et statue du gardien pétrifié de la Maison dorée.

La scène de l’incendie en particulier permet à Clemens Gadenstätter d’introduire les thèmes liés à l’identité, à la réalité et à la fiction qu’il développera ensuite tout au long de la pièce. Le Grand incendie de Rome est mis en scène selon différentes perspectives – Néron observant la ville en feu, Néron écrivant un poème épique sur l’incendie de Troie en guise d’allégorie, et enfin, la perception des citoyens romains en proie au feu bien réel. Les trois versions de cette scène apparaissent simultanément – en tant qu’objet esthétique, allégorie et réalité brutale. Nerone est une pièce qui ne cesse d’ébranler les frontières. Au premier abord, rien n’est clair ou réductible à une interprétation unique. En revanche, chaque action renvoie toujours à une autre.

L’idée centrale est au fond celle-ci : l’espace configure l’action qui s’y déroule, mais d’autre part, il est lui-même reconfiguré par chacune de ces actions. Ce bouclage ouvre de multiples possibilités d’intégration – de musique et de son, de langage (texte et narration), d’images et de film. Aucun élément n’est isolé mais fait toujours partie d’un réseau d’interactions. Dans Nerone, Gadenstätter crée des situations musicales et théâtrales lui permettant de donner des formes aussi diverses que possible à son projet esthétique majeur : rendre sensibles les qualités sémantiques de la musique. Le spectateur est soumis à un flux de perceptions hétérogènes, et par là constamment convoqué à adopter de nouveaux points de vue. Néron est un point fixe et fugace. Il conquiert le public et l’intègre à sa mise en scène imprévisible. « Nerone, explique Clemens Gadenstätter, est un moyen de présenter à la fois le théâtre dans le théâtre et la réalité terrifiante de notre monde moderne. »

quatre scènes-clés

1

Néron, un acteur qui imite l’Empereur. Le public agit en tant que public, mais est simultanément soumis aux décisions de l’empereur (ou de se représentation sur l’écran). Brutalité et impossibilité d’échapper à la confusion entre représentation et réalité. Que se passe-t-il lorsque l’existence et l’illusion sont déclarées égales en valeur ?

2

Les Jeux olympiques, tous remportés par Néron ! Si Néron n’est pas un novice dans les disciplines requises, il n’est pas non plus un « Olympien » à proprement parler. La corruption lui permet de créer une situation dans laquelle le rituel des tournois est transformé en démonstration de pouvoir réel et de folie divine. Le rituel sportif, dont l’objectif est de renforcer le prestige social et politique, cherche ici à se positionner à un niveau de réalité supérieur à celui du pouvoir politique — dont le « semblant » est admis comme tel. Le tournoi est reconstitué sur base d’un script où Néron, sans le savoir, se ridiculise : dans cette cette imitation, le rituel sacré d’affirmation de puissance devient une arlequinade dans laquelle l’empereur, se représentant lui-même, tue de vrais êtres humains. En termes structurels, cet épisode de tournoi opposera le musicien « mécanique » aux musiciens de l’ensemble, et sera toujours remporté par le musicien mécanique.

3

Rome en feu

— De manière perverse, cet événement est transformé par Néron en une pièce de théâtre dans laquelle il chante son propre poème épique sur l’incendie de Troie en regardant, de loin, la ville brûler. Il établit un lien entre la représentation de cet événement dans l’Iliade et l’incendie de Rome, ce qui lui permet d’ouvrir un espace d’inauthenticité totale. Dans cet espace, il voit le drame se dérouler devant ses propres yeux comme s’il s’agissait d’une « fiction réelle » : il a lui-même mis ce spectacle en scène. Les décisions de Néron portant sur la reconstruction de la ville après l’incendie rendent évidente la présence de deux niveaux de réalité : des mesures sophistiquées de protection contre le feu doivent protéger sa « Maison dorée », qui accueillera ses prochaines pièces et événements. Elle forme la scène, le décor dans lequel il va continuer à vivre. Le Grand incendie de Rome est mis en scène sous différentes perspectives – Néron observant la ville en feu, Néron écrivant un poème épique sur l’incendie de Troie en guise d’allégorie à celui de Rome, et enfin, la perception des citoyens romains en proie au feu bien réel.

4

La « Maison dorée » de Néron, conçue comme un théâtre

.

Les parcs sont ici conçus comme des « parcs d’attraction » pour les citoyens romains. Au centre, Néron est représenté dans sa « nudité divine » par un colosse de 40 mètres de haut. L’environnement de vie devient une scène. Et l’espace devient un objet artistique : la maison comme lieu accueillant différents espaces sociaux, permettant divers usages (villa d’empereur, parc d’attraction…) et comme objet purement esthétique.

über Nerone

Mit der Lyra in der Hand besingt er das brennende Rom. Wiewohl diese Szene vermutlich niemals stattgefunden hat, prägt sie bis heute die Rezeption einer gleichermaßen berühmten wie berüchtigten historischen Gestalt: Nero, von 54 bis 68 Kaiser des Römischen Reiches. Weitblickender Herrscher, Olympionike und vielseitiger Künstler auf der einen, Mörder, Brandstifter, Antichrist und Megalomane auf der anderen Seite. Und es sind eben jene Kontraste und Divergenzen, die aus dem Widerspruch des »zartbesaiteten Monstrums« erwachsen, die das Faszinosum Nero ausmachen. Das reale Subjekt als strapazierfähige Projektionsfläche: Jedem sein »eigener« Nero.

Die Potenziale ebenso wie die Komplikationen dieser widerstreitenden Lesarten greift Clemens Gadenstätter in seinem Bühnenstück Nerone auf. Nero ist hier zugleich er selbst, wie auch seine zahlreichen Repräsentationen: Imperator und Künstler zu selben Zeit, am selben Ort. Thema und Setting von Nerone ist demzufolge die Bühne, wobei damit aber nicht allein der theatrale Raum gemeint ist. Stattdessen erweitert Gadenstätter die Bühne in Richtung gegenwärtiger Alltagswahrnehmung und -erfahrung. Über den Ort des repräsentativen »Schau-Spiels« hinaus, wird sie zum vieldeutigen Handlungs- und Aktionsraum, stets oszillierend zwischen Authentizität und Schein, zwischen Faktizität und Narrativ.

Simultan in diversen (sozialen) Räumen, Rollen und Funktionen zu existieren und sich diesen Umgebungen »mimetisch« anzupassen, ist längst zur Conditio humana des modernen Menschen geworden. Um dem Anspruch dieser umfassenden Anteilnahme gerecht zu werden, bedarf es einer gewissen Bereitschaft zur »Persönlichkeitsspaltung«. Wir sind ebenso real wie virtuell, agieren gleichermaßen unmittelbar und durch Medien vermittelt. In Nerone wird eine historische Figur zum Sinnbild dieser »Verwandlungskunst«. In vier »dramatischen Knoten« werden unterschiedliche Konstellationen eines Vexierspiels zwischen den Identitäten erforscht. In diesen Szenen taucht Nero in verschiedenen Zusammenhängen auf: Als Schauspieler, der den Kaiser darstellt. Als Olympionike, der den erhabenen Wettkampf zur Selbstinszenierung missbraucht. Als Beobachter des Großen Brandes von Rom. Als zum Standbild erstarrter Hüter des Domus Aurea.

Insbesondere die Brandszene verdeutlicht das Spiel mit Identität, Realität und Fiktion, das Clemens Gadenstätter in Nerone entfaltet. Der Brand Roms wird hier aus verschiedenen Perspektiven inszeniert: Nero, der auf die brennende Stadt sieht. Nero, der ein Epos über den Brand Trojas als Sinnbild des in Flammen stehenden Rom bemüht. Und schließlich die Erfahrung des ganz realen Feuers durch die römischen Bürger. Damit erscheint die Szene simultan in drei Lesarten: als ästhetisches Objekt, als Allegorie und als brutale Realität.

Nerone ist eine Arbeit, die sich durchweg auf Grenzlinien bewegt. Nichts ist von vornherein eindeutig und auf eine konkrete Bedeutung reduzierbar. Im Gegenteil: Jede Handlung ist immer auch die Repräsentation einer anderen. Die zentrale Idee des Stücks ist dementsprechend die eines Raumes, der einerseits die in ihm stattfindenden Handlungen beeinflusst, zudem aber auch durch eben jene Handlungen geformt wird. Diese Wechselwirkung eröffnet ein weites Feld an Möglichkeiten der Arbeit mit verschiedenen Medien: Musik, Klang, Sprache, Text, Narration, Bild, Film. Kein Element steht dabei für sich, sondern ist immer Bestandteil einer Interaktion.

In Nerone entwirft Gadenstätter musikalisch-theatralische Situationen, in denen er sein ästhetisches Konzept einer Durchleuchtung der semantischen Qualitäten von Musik in denkbar vielschichtige Kontexte setzt. Der Zuschauer gerät in einen Bannkreis heterogenster Wahrnehmungen und ist dazu aufgefordert, sich immer neu zu positionieren. Nero ist dabei der flüchtige Fixpunkt: Er beherrscht das Publikum und macht es zugleich zum Mitspieler seiner unwägbaren Inszenierung. »Nerone«, sagt Clemens Gadenstätter, »ist ein Stoff, der Theater im Theater ist – und gleichzeitig die erschreckende Realität unserer heutigen Welt«.